New breakthroughs give agriculture technology a leap in weather forecasting

The science behind meteorology has changed. Farmers’ need for accurate weather forecasting has not.

A revolution in small satellites and computing capabilities is pushing the boundaries of weather data collection and forecasting. The breakthroughs benefit businesses across industries, maybe none more so than AgTech application service providers. Global observations and the promise of localized forecasts can help them provide standout solutions the world over.

A turning point for weather forecasting

The United States’ Mid-Atlantic region woke up on Sunday, February 18, 1979, to a run-of-the-mill winter forecast: frigid temperatures with a chance of four to six inches of snow. But by nightfall, conditions were anything but ordinary.

A surprise blizzard stunned communities and engulfed some parts of the East Coast under as much as 20 inches of snow. Hundreds were stranded, emergency services struggled to answer distress calls, and some hospitals ran short on supplies through the night. By Monday morning, the Washington, D.C.-Baltimore area was at a standstill and New York City’s airports were closed. In the end, 13 people had died, according to a report from the time.

After the blizzard passed, forecasters and researchers gathered to determine what went wrong, according to a report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. How did a mammoth storm suddenly appear without warning? They couldn’t let this happen again.

As it turns out, meteorologists underestimated the storm’s severity because of technological limitations. The low-resolution models of the time, not to mention the scarcity of satellite data, made it challenging to predict even storms of historic proportions, according to The Washington Post. Hindsight, at least, is 20-20.

Since the President’s Day Storm of 1979, meteorology has come a long way. “As technology advanced,” said Asma Toroman, a product marketing manager at Spire Global, “so has weather forecasting.”

A revolution in satellite technology, as well as developments in computing and statistical capabilities, have changed weather forecasting for the better. Forecasters can now predict where a hurricane will be in three days more accurately than their counterparts forty years ago could predict where a storm would be after one day, according to a report in Science Magazine. Similarly, current five-day weather forecasts are as reliable as one-day estimates used to be.

This overall improvement, the report’s researchers found, “provides numerous societal benefits, from extreme weather warnings to agricultural planning.”

“This is not your grandparent’s weather.”

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Weather technology takes off

There have been three major breakthroughs in the history of weather satellite technology, and we are living in one of them, said Dr. Alexander MacDonald, Spire’s chief science officer.

The first breakthrough came when Sputnik 1 successfully orbited the Earth in 1957, propelling humanity into the space age. The second followed in the 1960s with the development of geostationary satellites, which provided great advances in communications and Earth observation. As for the third, it’s happening right now with the development of small, inexpensive satellites capable of many groundbreaking applications.

“A company like Spire can build a little, tiny satellite the size of a wine box,” Dr. MacDonald said, referring to nanosatellites, “and take super sophisticated measurements that have much more vertical resolution than those old microwave profiles that they used before.”

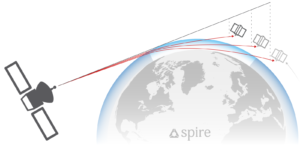

Spire’s satellites can capture high-resolution observations because they make radio occultation measurements. This sensing technique—also known as GNSS-RO or GPS-RO—calculates the refraction of geospatial satellite signals as they pass through the atmosphere. Because the degree of refraction depends on physical properties like temperature and water vapor, radio occultation measurements reveal precise weather-related data about multiple layers of the atmosphere.

“Radio occultation provides us an incredible precise understanding of global atmospheric conditions at any time,” John Lusk, Spire Global’s vice president and general manager, told USA Today for a special report on agriculture and technology.

Radio Occultation is a technique used to measure the angle a radio signal bends as it passes through the Earth’s atmosphere.

Better yet, because these nanosatellites are many times cheaper than traditional satellites, Spire was able to launch a constellation of these shoebox-sized devices and let them sense Earth’s weather conditions. With just 86 satellites, Spire’s fleet recently collected ten thousand measurements from around the entire globe in a single week.

Altogether, this system offers both worldwide coverage and fine detail. Or, as Dr. MacDonald put it: “In terms of price versus performance, radio occultation is the best.”

And it’s not just us who think so. The United Kingdom’s Met Office found in a recent study that assimilating Spire’s radio occultation data offers “a substantial forecast benefit.”

As Spire launches more nanosatellites, earth observation will continue to improve, adding new information to data collected by aircraft sensors and national and international institutions. This growing resource will support global weather predictions, from sea to sky, focusing on a range of variables, such as air temperature, wind speeds, precipitation, dew point temperature, soil moisture, and specific humidity.

“This is not your grandparent’s weather,” Ms. Toroman said.

“Radio occultation provides us an incredible precise understanding of global atmospheric conditions at any time.”

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Strength in numbers

The volume and detail of weather data we capture today reveal a highly accurate picture of atmospheric conditions, perfect for feeding into forecasting models. And as data collection has improved, models have also experienced seismic breakthroughs. Advances in computing power and statistical capability are unlocking powerful forecasting models, and artificial intelligence developments are hinting at an even more exciting future.

Models forecast weather conditions by solving physics equations, just like you might predict where a car will be in an hour if you know its current speed, only far more complex. As computing power has multiplied, experts have been able to crunch more numbers and equations for increasingly precise forecasts.

Weather scientists improve these models by running them over time and monitoring their performance. Did it overestimate temperatures at 10,000 feet above Jakarta? How accurate were wind speed forecasts in the Bay of Bengal? By adjusting for any shortcoming, scientists can continuously improve models.

Spire has developed ways of using multiple global models to optimize forecasts, said Fabio Mano, a weather product manager at Spire. We start by adding radio occultation data into the initial states that feed the models. Then we run all the models and prioritize their strengths in different regions and situations to help enhance the overall result.

And developments in artificial intelligence point to the possibility of improved forecasting. “Machine learning and neural networks can help identify model uncertainties, perform bias corrections, and automate the forecast process,” according to the previously mentioned report from Science Magazine.

Weather + AgTech: The ultimate power couple

Breakthroughs in weather predictions support businesses across industries, but maybe none more so than agriculture and the companies that support farming. For as long as there have been farmers, there have been forecasters predicting the weather for them using the latest techniques.

Around 700 B.C., the Greek poet Hesiod linked astronomical and weather events in his practical guide to farming, “Works and Days.” Medieval Europeans turned to lore and legend before the scientific revolution. And in 1792, The Farmers’ Almanac published its first issue and long-range weather predictions based on, among other variables, sunspot activity.

While the science behind meteorology has changed, farmers’ need for accurate weather forecasting has not. That is precisely why the recent developments in weather forecasting we surveyed above can be such an asset for AgTech application service providers. They can help companies stand out in the booming marketplace, bursting with thousands of companies and billions of dollars of investment.

Radio occultation measurements and an advanced model help add an extra degree of precision to the forecasts, explained Mr. Mano. Spire’s solutions, in particular, offer an understanding of global and local atmospheric conditions, both of which can be highly valuable to AgTech application service providers’ customers.

Thanks to its constellation of satellites, Spire can collect uniform, detailed weather data around the world. This capability helps offer global clients high-quality information across their agricultural operations, helping save them from relying on a patchwork of weather services, some that may be less reliable than others. Global readings will only grow as we launch new satellites and measure different weather parameters. For example, soil moisture readings are now available—a particularly useful measurement to offer the modern farmer.

As our understanding of global atmospheric conditions expands with every new observation, so too does the ability to make accurate local weather predictions. The phenomena are inextricably linked. We are progressing towards forecasts that are more specific to customers’ needs and locations.

The connection between farmers and forecasters will remain as critical as ever, with application service providers strengthening the bond.

A step in the right direction

Dr. MacDonald started his career around the time of the 1979 President’s Day storm, working as a forecaster for Air Force pilots. We had no skill back then, he joked, but today “we have a solution that’s really valuable.”

It’s a good thing, too. Weather conditions “dominate every aspect of our lives,” he pointed out.

Although we can’t change the weather—yet—we can optimize for it. Airlines can adapt departure times to avoid delays. Towns can schedule the production of renewable energy with weather patterns. And weather data can help optimize route planning in the maritime industry for cost, fuel, and time savings.

We expect to see more of these gains across industries as experts push the boundaries of weather sensing and launch transformative forecasting models.

Written by

Written by