GNSS interference report: Russia – Part 2 of 4: Crimea and the Black Sea Region

Written by:

Travis Turgeon

Independent Investigative Writer

Tjaša Pele

Digital Marketing Manager, Spire Aviation

Antoine Cayphas

Data Scientist, Spire Aviation

Written by

Written bySpire Global

This four‑part series delivers concise, data‑backed snapshots of GNSS interference activity in and around Russia.

Each installment pairs open‑source reporting with Spire’s LEO-based ADS-B and RF constellation, providing decision‑grade insight that goes well beyond public jamming maps like gpsjam.org.

Part 2 looks at multiple GNSS interference events in March and April 2025, when Russian forces redeployed jamming systems from Crimea to frontline zones in Kherson Oblast – disruptions that were independently validated through satellite-based monitoring.

Crimea and the Black Sea Region

Russia’s use of electronic warfare (EW) around Crimea and the Black Sea region has shifted from isolated jamming events to a dynamic, mobile strategy that is actively shaping battlefield conditions in southern Ukraine.

Once an epicenter of Russia’s GNSS interference operations, Crimea remains heavily fortified. However, key systems, such as Pole-21 satellite jammers, are being strategically redeployed to more contested areas when necessary, particularly along the Kherson–Mykolaiv corridor. This shift represents a tactical evolution: GNSS jamming is no longer a static form of disruption for Russia, but a responsive tool used to adapt to drone-driven threats and front-line pressure.

Interference in this region not only confuses ISR drones and aircraft positioning, but it has now become a direct factor shaping military decisions, operational tempo, and tactical planning on both sides of the conflict.

The key takeaway? EW in the Black Sea is no longer fixed. It’s mobile, adaptive, and synced to the rhythms of modern, drone-intensive warfare.

Summary

- Location: Crimea and Kherson Oblast, Ukraine

- Activity: Strategic relocation of Russian air defense and GPS jamming systems, including Pole-21

- Date highlight: March-April 2025 – Electronic Warfare (EW) systems moved from Crimea to Kherson; targeted destruction of Russian jammers on April 14.

- Impact zones: Southern Ukraine frontlines, Black Sea coastal regions, and surrounding airspace

Real-world incident: Frontline jamming & tactical response

In late March 2025, resistance sources affiliated with the ATESH movement reported that Russia was moving Pole-21 GPS jamming systems out of southern/central Crimea and redeploying them to Kherson Oblast. The reports were interpreted as an effort to reinforce EW coverage near the increasingly active frontlines around Oleshky and the Dnipro River delta, where Ukrainian drone strikes and precision targeting are intensifying.

The Pole-21 system is designed to jam GNSS signals and communications links, particularly those used by UAVs and guided munitions. Open-source GPS interference maps from gpsjam.org showed a corresponding shift in GNSS disruptions during this time, with signal degradation appearing in areas matching reports of newly-placed Russian air defense systems near the border.

Then, on April 15, Ukraine reportedly responded with a drone strike that destroyed a Borisoglebsk-2 jamming complex near Kamianske in the Kherson region. According to a video released by Ukraine’s Operational Command South, the strike used two UAVs – one to disable the system and the second to destroy it entirely. The Borisoglebsk-2 is one of Russia’s most advanced EW platforms, capable of conducting up to 30 simultaneous jamming tasks, and has an estimated value of $200 million.

This event marked a rare publicly visible instance of Ukrainian forces successfully targeting a high-value EW system deep behind the lines. While the exact timing of the strike remains unconfirmed, its release signaled Ukraine’s growing emphasis on degrading Russian jamming capabilities to regain tactical airspace advantage.

Although the operational impact of the strike is difficult to confirm through open-source maps alone, the event adds an important dimension to the evolving EW landscape in southern Ukraine, highlighting both the vulnerability of mobile Russian jamming platforms and the increasing precision of Ukrainian UAV strikes.

Spire satellite validation

What Spire saw

This section draws on data from Spire Aviation’s GNSS interference monitoring constellation, specifically filtered to highlight confirmed, high-confidence jamming activity over southern Ukraine and Crimea.

We limited the analysis to:

- Records where NACp_q05 = 0, indicating a complete loss of horizontal position accuracy at the 5th percentile – a strong signal of GNSS degradation

- Hexes with ≥5 aircraft reporting, to eliminate statistical noise or single-point anomalies

This filtering ensured we captured only repeatable, aircraft-validated interference events, providing a more conservative and operationally meaningful dataset.

March 12-28, 2025

During this window, GNSS interference was heavily concentrated over western Crimea, including Sevastopol, Yevpatoriya, and Saky. These locations are consistent with known Russian EW deployments and match historic interference patterns visible in public datasets.

Figure 1 shows this pattern clearly: jamming is restricted to the Crimean peninsula, with no detectable interference north of the border in Kherson Oblast or along the Dnipro Delta front.

Figure 1: GNSS interference data from March 12 – March 28, 2025

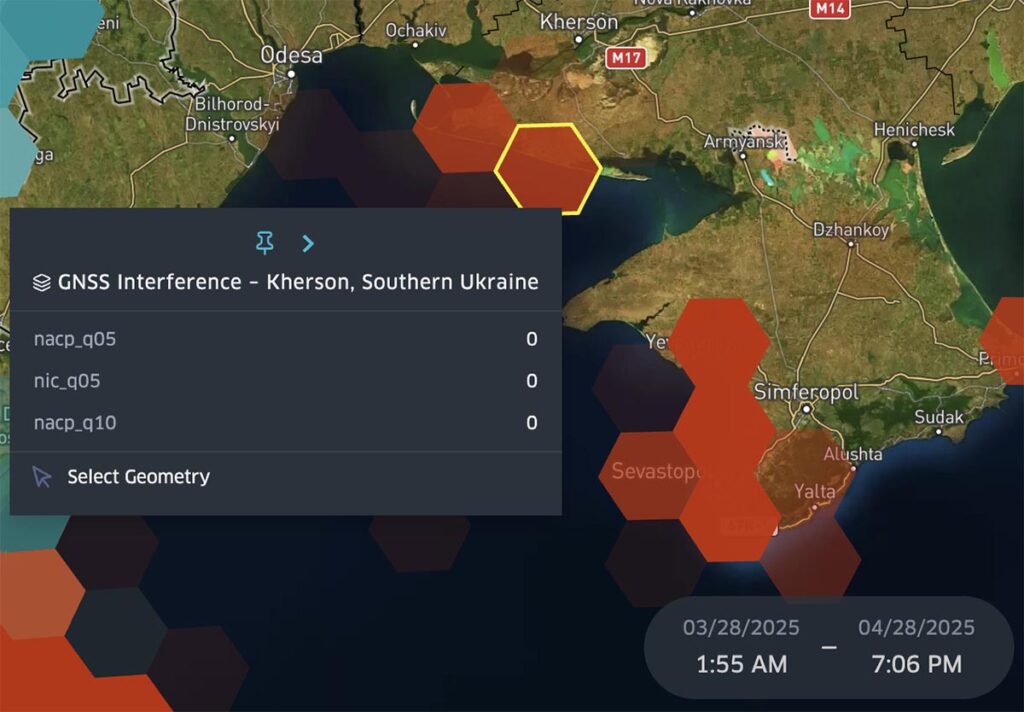

March 28-April 28, 2025

A sharp geographic shift occurs toward the end of March. Interference expands north and west of Crimea, appearing for the first time in Spire Aviation’s dataset near southern Kherson Oblast, including airspace over Armyansk and the Black Sea coastline.

This timing aligns with open-source reporting of Russian EW asset redeployments from Crimea to the southern front. Specifically, partisan networks and military analysts reported that Pole-21 systems were being repositioned to defend against increasing Ukrainian drone and strike activity near the Kherson-Mykolaiv axis.

Figure 2 shows interference activity now spanning both Crimea and southern Ukraine, suggesting that mobile jamming systems were either relocated or temporarily co-deployed near the border.

Figure 2: GNSS interference data from March 28 – April 28, 2025

Still, one key anomaly stands out. Between April 14 and April 16, jamming activity over Kherson Oblast disappears entirely – a brief blackout during an otherwise continuous interference period. This 48-hour blackout directly precedes the April 15 release of video footage showing a Ukrainian drone strike on a Borisoglebsk-2 jamming system near Kamianske.

While Spire Aviation’s dataset cannot confirm the exact cause of the lapse, and the drone impact site lies inside inactive Ukrainian airspace, the timing is consistent with either a system loss or a tactical shutdown of local EW operations in response to the intrusion. The interruption highlights how even within sustained jamming periods, interference can pause, reposition, or retreat based on evolving threat conditions.

Figure 2a: GNSS interference data from April 14 – April 16, 2025 (48-hour blackout)

April 28-May 12, 2025

A sudden drop in interference is observed again starting late April. Hexes across southern Kherson Oblast and the adjacent coastal region go dark with no qualifying GNSS degradation detected, despite ongoing aircraft traffic present.

Figure 3 highlights this change. Jamming remains visible in Crimea but disappears entirely north of the peninsula, suggesting either a temporary EW stand-down, a redeployment of mobile assets, or a lull in active jamming missions.

Figure 3: GNSS interference data from April 28- May 12, 2025

The gaps observed, which were both brief and sustained, showcase the value of high-resolution satellite data in capturing not only GNSS interference, but its timing, volatility, and operational behavior.

The impact of Spire’s satellite data

Spire Aviation’s data provides critical insight into the operational rhythm of electronic warfare, not just its presence. While public sources can show that jamming occurred, they cannot reliably pinpoint:

- When interference intensifies

- Where jamming systems relocate

- When and where interference ceases

In this case, Spire Aviation’s data reveals a three-phase evolution of GNSS jamming across the southern front:

- Pre-relocation: Static interference confined to Crimea

- Frontline expansion: Interference spreads across Kherson Oblast airspace

- Operational pause: Jamming vanishes abruptly from high-priority airspace

This progression offers a strategic lens into real-world EW behavior, illustrating how interference not only expands and persists, but also retreats, pauses, and adapts in response to battlefield conditions.

Interference pattern and attribution

Spire Aviaton’s GNSS telemetry reveals a clear three-phase evolution of interference in southern Ukraine between March and May 2025:

- Localized disruption over Crimea (March 12–28), consistent with static EW installations

- Expansion into Kherson Oblast (March 28–April 28), suggesting mobile deployment of Pole-21 systems

- Abrupt interference pauses, including a brief 48-hour blackout (April 14–16) and a sustained outage (April 28–May 12), showing either tactical repositioning, system loss, or command-level deactivation

These patterns align with both open-source reporting of EW system movement and Ukraine’s tactical countermeasures, but only Spire Aviation’s data captures their timing, location, and duration with aircraft-based precision.

Operational impact

GNSS jamming across southern Ukraine directly affects:

- ISR and UAV operations, by degrading satellite-based navigation and targeting

- Civilian air traffic, especially at low altitudes along contested corridors

- Battlefield coordination, where digital targeting and movement depend on reliable GNSS data

The presence, and sudden absence, of interference in key zones reflects both Russia’s evolving EW strategy, as well as moments of vulnerability. Spire’s high-resolution monitoring enables early detection of these changes, improving situational awareness for aviation, defense, and civil resilience stakeholders.

What’s next

Part 2 investigated Crimea and the Black Sea, where Ukrainian drone strikes are thought to have disrupted and reshaped Russian jamming operations. In Part 3, we’ll shift focus to Moscow and major urban zones, where short-duration, high-intensity jamming is increasingly used to defend high-value infrastructure from long-range UAV threats.

Using Spire Aviation’s GNSS interference data, we’ll analyze how mobile jamming assets are deployed during high-alert periods, including Victory Day, and how these urban interference patterns impact both military operations and civilian aviation.

Get in touch to explore Spire’s GNSS‑interference data feed or request a demo:

Continue reading our GNSS interference report series

01: GNSS interference report: Russia – Part 1 of 4: Kaliningrad & the Baltic Sea

02: GNSS interference report: Russia – Part 2 of 4: Crimea and the Black Sea Region (current)

03: GNSS interference report: Russia – Part 3 of 4: Moscow and major urban zones

04: GNSS interference report: Russia – Part 4 of 4: Black Sea & Romanian airspace