Sanctions on Russia as it presses in on Ukraine

The current Russian invasion of Ukraine is taking place on land long wracked by war. The events that have occurred over the last month bring us to look back on what has come before, including some of the worst episodes of 20th-century European history.

But there are also some aspects of the current war that are unique to our age. The widespread availability and use of new advances in communications technology, especially by the government of Ukraine and its supporters abroad, has meant far greater real-time information is available. Likewise, the integration of national economies within the predominant global economy has made the impact of economic sanctions more powerful and faster acting.

The entire conflict is occurring at a time when there is an unparalleled ability to track not only what is happening on the battlefield but also the corollaries—both public and obscure—taking place around the world. From geolocating battles to tracking supply flights to monitoring seaborne trade, there’s an astonishing ability for people anywhere to plug into information sources in ways not possible just decades ago.

The kind of maritime data that Spire can provide is one aspect of this dynamic. With real-time AIS, a crucial aspect of the conflict—the flow of goods in and out of Russia after the draconian sanctions that many of the world’s leading economies imposed on it—can be monitored in real time. This ability to follow events is a piece with other aspects of this very modern military encounter.

What the frontlines tell us

From news reports to first hand accounts, people across the globe are able to continuously stay informed through a vast number of live updates. The particulars of the battlefield are immediately available in a profoundly new way. Individuals, even soldiers, upload TikTok, Twitter, and Instagram Live posts. Individuals ranging from retired generals to, in the American parlance, “grunts” with military logistics experience comment on what is happening on the ground throughout Ukraine.

Outside of Ukraine, the Amsterdam-based author and analyst Stijn Mitzer, using visual evidence and geolocating, has become a go-to source for information regarding equipment losses in the war via the website Oryx. The significant uptick of NATO signals intelligence (SIGINT) aircraft sorties along the Ukrainian border has been noted by following easily accessible live flight trackers, and the dispersing of Russian oligarchs’ super yachts as they seek safe ports has become, according to an article in the Washington Post, “Schadenfreude at sea: The Internet is watching with glee as Russian oligarchs’ yachts are seized.” The flights of private jets out of Moscow have likewise been easily monitored.

Sanctions as confrontation

The hot war that Ukraine is bearing the brunt of is rightly the focus of the world’s attention, but the imposition of economic sanctions against Russia is a vital part of the whole.

Given the reality that Russia is believed to have over 6,000 nuclear warheads at its disposal, while NATO’s three nuclear powers (France, the United Kingdom, and the United States) have a similar number at their disposal, much of the diplomatic effort outside of Ukraine has been to limit the possibility of a direct armed confrontation between Russia and NATO.

The stand-in for military interaction is an economic proxy war, with economic sanctions being brought to bear on the ability of the Russian state to engage in an extended foray into Ukraine.

Leashing Russia through sanctions

This brings us to monitoring the impact of the sanctions. The fact is that Russia has seen its ability to benefit from economic cooperation radically curtailed, both financially and physically. Within days, many nations closed their airspace to Russian flights. In addition, many aircrafts in Russia’s civilian fleet are leased from companies abroad (especially Ireland), which means that the ability to keep planes flying in Russia will be severely curtailed due to a lack of spare parts and software updates. Likewise, most European nations bordering Russia, with the exception of ally Belarus (which also faces economic sanctions), have made land-border crossings difficult.

Although Russia is attempting to gain the support of India and China to survive the current sanctions, the reality is that the European Union is Russia’s most natural and largest trading partner. Nearly 50% of its high-tech imports were from the EU (and another 20% from the United States). Europe is the biggest importer of petroleum products from Russia; replacing that market will be difficult given the long distances and lack of infrastructure investment involved. Moscow is nearly 6,000 kilometers from Beijing and over 4,000 from New Delhi; in contrast, Berlin is less than 2,000 and Kyivis less than 1,000.

Thus, seaborne shipping is critical to the Russian economy and guarding against sanction violations is vitally important. Economic blockades always have cracks and limiting them is always a challenge.

The picture so far

The picture so far appears to show that, at least in the case of ships under the flag of the United States, the sanctions are being heeded. This map from April 5th shows that there are no US-flagged ships near any Russian ports:

No US Flagged Ships (in Red) Near Russian Ports 4/5/2022

Data Source: Spire Maritime

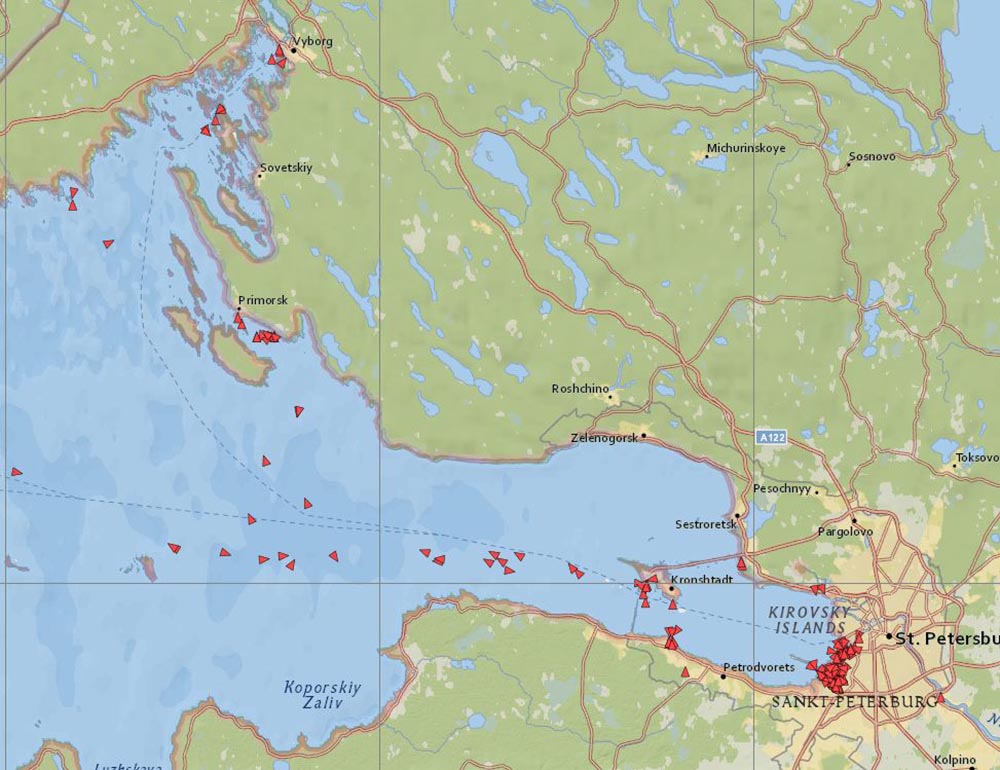

This aggregate situation can be seen in detail with the current maps of specific Russian ports. The Port of St. Petersburg shows the lack of US-flagged ships at this vital transportation hub that serves western Russia, where 75% of the nation’s population lives:

Gulf Of Finland: Russian Ports of St Petersburg & Vyborg:

No US Flagged Ships In the Area on April 5, 09:14 am GMT

Data source: Spire Maritime

| Antigua and Barbuda | 3 | 2% |

| Azores | 1 | 1% |

| Bahamas | 2 | 1% |

| China | 1 | 1% |

| Croatia | 1 | 1% |

| Denmark | 2 | 1% |

| Dominica | 1 | 1% |

| Gibraltar | 1 | 1% |

| Liberia | 3 | 2% |

| Madeira | 2 | 1% |

| Malta | 8 | 5% |

| Marshall Islands | 5 | 3% |

| Norway | 1 | 1% |

| Panama | 3 | 2% |

| Russian Federation | 122 | 78% |

| Grand Total | 156 |

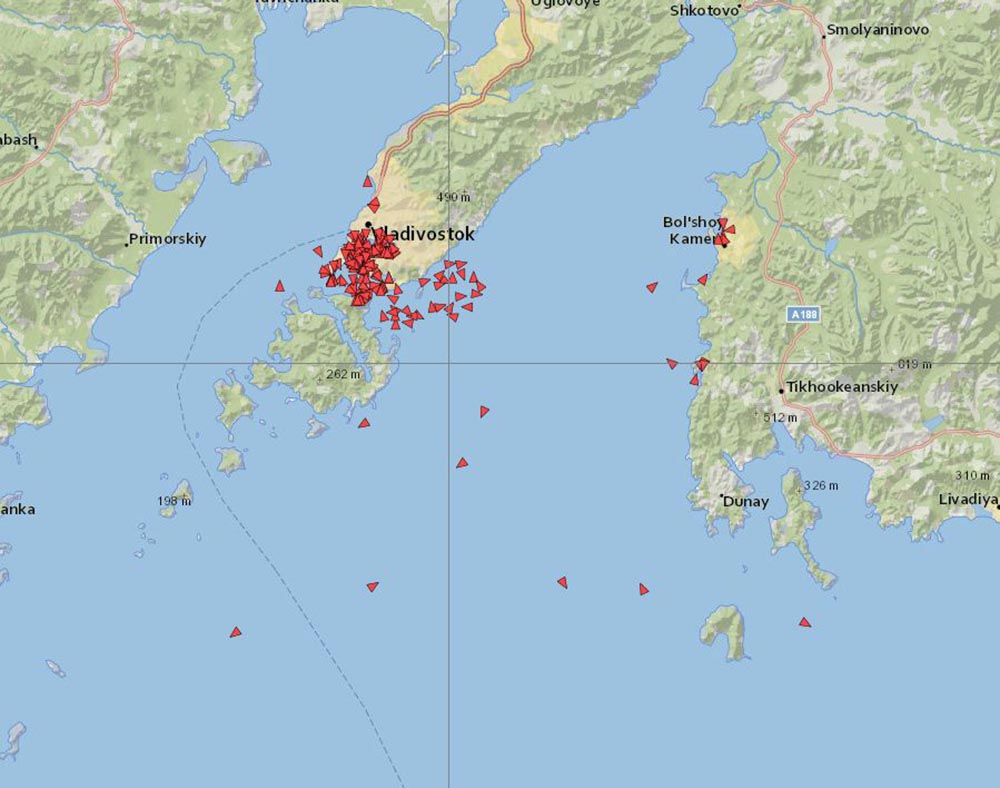

Likewise, the primary Russian Pacific port of Vladivostok can be seen here:

Port of Vladivostok: largest Russian Port in the Pacific:

No US Flagged Ships In the Area on April 5, 09:24 am GMT

Data Source: Spire Maritime

| Antigua and Barbuda | 3 | 2% |

| Azores | 1 | 1% |

| Bahamas | 2 | 1% |

| China | 1 | 1% |

| Croatia | 1 | 1% |

| Denmark | 2 | 1% |

| Dominica | 1 | 1% |

| Gibraltar | 1 | 1% |

| Liberia | 3 | 2% |

| Madeira | 2 | 1% |

| Malta | 8 | 5% |

| Marshall Islands | 5 | 3% |

| Norway | 1 | 1% |

| Panama | 3 | 2% |

| Russian Federation | 122 | 78% |

| Grand Total | 156 |

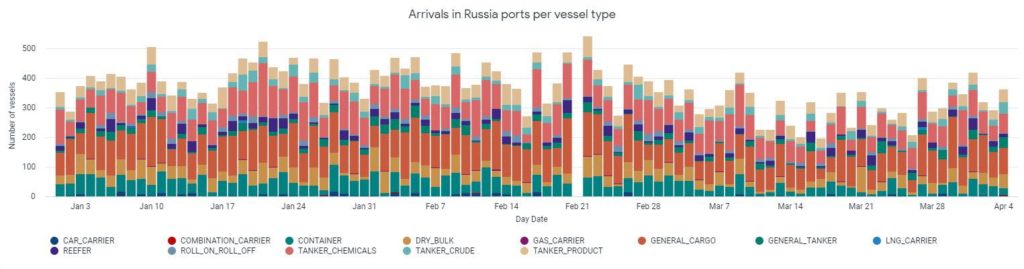

Put together, what can be seen over the last two months is a clear decline in the number of ships arriving at Russian ports since the invasion was unleashed on February 24th. This development can be seen in great detail across different economic sectors, with this chart covering 2022 thus far:

Cargo Ships Arriving at Russian Ports Average 397 per day prior to Feb 24 (First US + Allies Sanctions Announced) and 318 per day since then, update 5/4/2022

The hardest export nut to crack

The clearest and most potent missing aspect of the current sanctions is the exemption of oil and gas products from Russia to Europe, especially to the biggest consumer, Germany. Only the Baltic States and the United States have thus far cut off gas shipments, a fact that Ukraine’s government is not-so-subtly encouraging the rest of Europe to do.

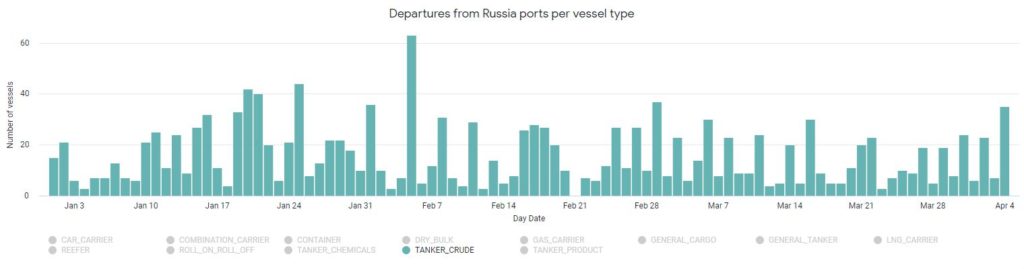

Although the more high-profile delivery system for Russian natural gas to Europe is via pipelines, tankers are also a crucial element of Russia’s energy-export infrastructure. Although there is some evidence that Russian oil tankers are beginning to play cat-and-mouse games by turning off transponders for extended periods, it is clear that the dwindling market for Russian oil is having an effect. The number of crude oil tankers leaving Russian ports has clearly dropped in recent weeks:

Crude Oil Tankers Departing Russian Ports Average 17 per day to per day (after US sanction announced on March 8) 4/5/2022

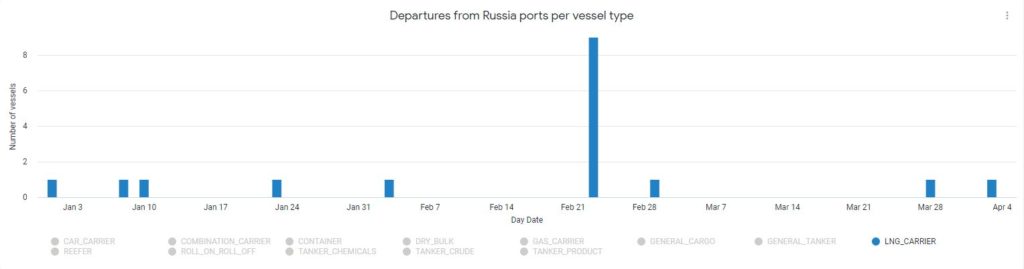

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) departures saw a spike immediately before the invasion but traffic has now fallen:

LNG Departure Data Over a 3 months 4/5/2022

With energy products being virtually the only current significant source of cash income for the Russian economy—prior to the war these represented over 40% of Russian exports—tracking their shipment via tankers will be of great interest to Western intelligence agencies that are tasked with enforcing sanctions.

Areas of interest to track

Several key areas will be important to the outcome of the war in Ukraine.

Trade with the East

One of the most important factors regarding economic pressure on Russia is how robust China will be in supporting its ally. While China has not joined in sanctioning Russia, a failure on its part to pick up the slack demand for Russian products due to both the sanctions and consumer boycotts of Russian goods will be important.

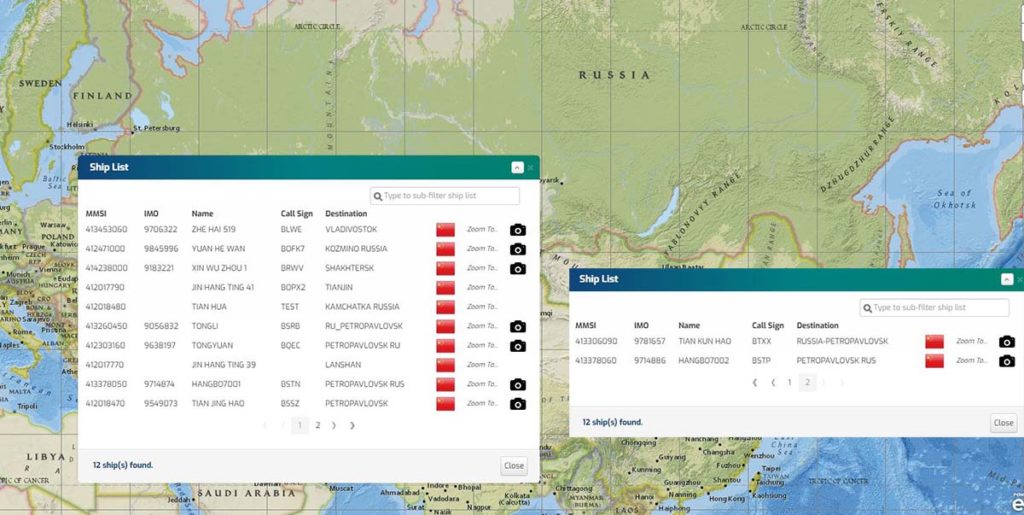

China is Russia’s largest export customer, accounting for about 15% of its sales, though this is less than the European Union’s portion. Given the vast distances between Russia’s industrial base in the west and China, overland transport is not nearly as efficient as seaborne shipping. Will there be an increase in Chinese ship traffic in Russian waters that shows an uptick in Chinese imports from a now beleaguered Russian economy? Here’s the current situation:

29 Russian Flagged Ships Near Ports in China April 5, 09:58 am GMT

Data Source: Spire Maritime

Ships with a Chinese Flag in Russian waters April 5, 10:14 am GMT

Data Source: Spire Maritime

An isolated piece of Mother Russia

Another specific area to keep an eye on is Kaliningrad, a Russian province bordered by Poland and Lithuania that does not share a contiguous border with any part of Russia. Poland and the Baltic States have closed their airspace to Russian planes and are attempting to close their land borders as well, which would leave the Port of Kaliningrad as the only way to move goods in and out of the region.

Long a Major Piece on the Chessboard

Finally, the Black Sea is on the frontlines of the war. It is a body of water that has long played a fundamental role in Russian statecraft: “Moscow sees the Black Sea region as vital to its geoeconomic strategy: to project Russian power and influence in the Mediterranean, protect its economic and trade links with key European markets, and make southern Europe more dependent on Russian oil and gas. Keenly aware of the potential for instability to flow from the Middle East into Russia—particularly the North and South Caucasus—Russia also sees this body of water as an important security buffer zone, protecting it from the volatility that could emanate from further south.”

It is also Ukraine’s only way to access the world’s oceans.

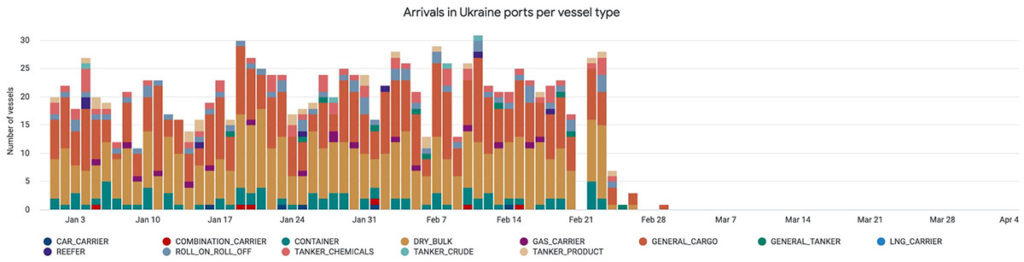

Russia has mined areas near the Ukrainian coast and there have been incidents of noncombatant ships being fired upon. The result for Ukrainian shipping, which is vital to the world’s food supply, has been stark:

Ukraine port activity-arrivals: Updated 4/4/2022

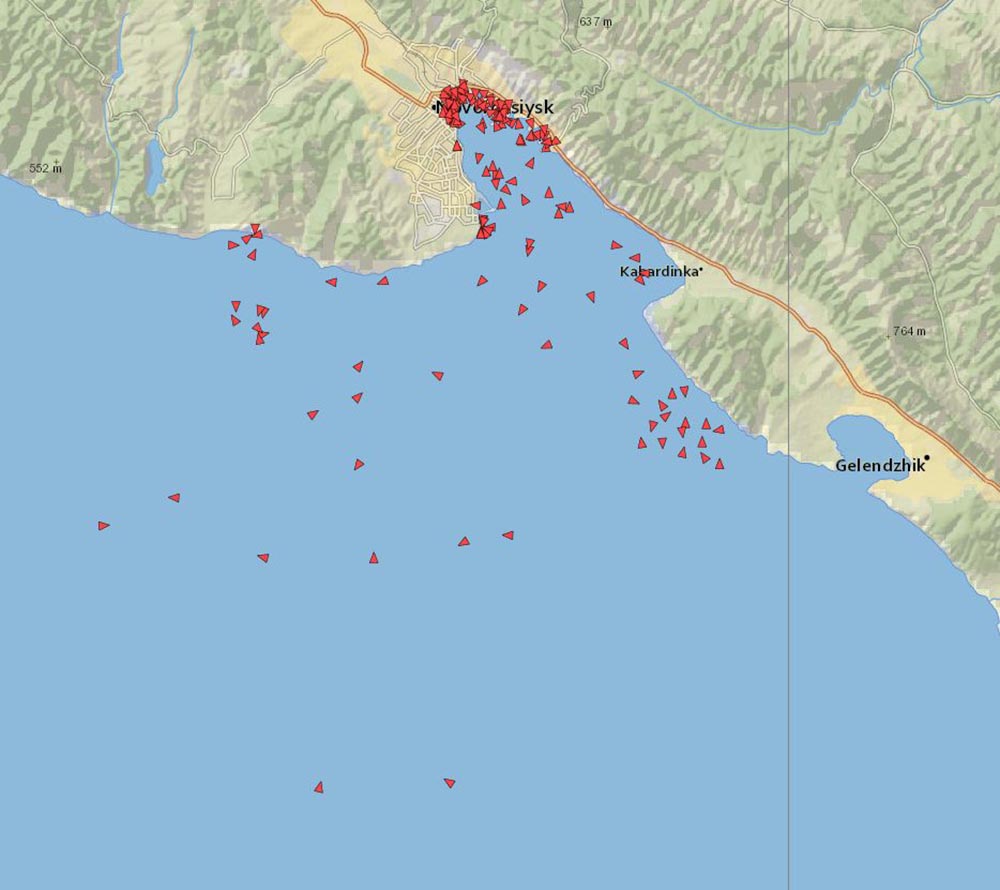

This is not the case for ongoing traffic from Russia’s primary Black Sea port of Novorossiysk:

Port of Novorossiysk: Russia’s Primary Black Sea Port:

No US Flagged Ships In the Area on April 5, 09:35 am GMT

Data Source: Spire Maritime

| Barbados | 2 | 1% |

| Belize | 2 | 1% |

| Cameroon | 1 | 1% |

| Comoros | 1 | 1% |

| Greece | 3 | 2% |

| Liberia | 4 | 2% |

| Madeira | 1 | 1% |

| Malta | 7 | 4% |

| Marshall Islands | 8 | 5% |

| Norway | 1 | 1% |

| Palau | 2 | 1% |

| Panama | 13 | 8% |

| Russian Federation | 122 | 71% |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 | 1% |

| Sierra Leone | 1 | 1% |

| Tanzania | 1 | 1% |

| Togo | 1 | 1% |

| Turkey | 1 | 1% |

| UK | 1 | 1% |

| Grand Total | 173 |

Activities in the Black Sea will be an important aspect of the conflict and its resolution, since capturing Ukraine’s southern coast was one of Russia’s initial goals when the invasion was launched, though capturing Odesa now seems very unlikely.

Action over time

The trajectory of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has already been surprising. The expectation shared by many—especially Vladimir Putin and the Russian military command—that Ukraine would fall quickly has been thoroughly dashed, with Russian forays towards Kyiv and Odesa decisively thwarted.

The next phase of the war, charitably Russia’s Plan B, is not commencing. When US President Joe Biden announced the first round of sanctions soon after the invasion began he stressed that it would take time for them to have their full impact: “This is going to take time. [Putin] is not going to say ‘oh my God, these sanctions are coming, I’m going to stand down.’ He’s going to test the resolve of the West to see if we stay together. And we will.”

One way to gauge their success is by keeping a detailed eye on shipping traffic in and out of Russia’s key ports and other nautical hotspots with AIS data.

UNICEF

Our thoughts continue to be with the people of Ukraine. Please donate to UNICEF. UNICEF is included in CharityWatch’s list of Top-Rated Charities, with every dollar spent, 88 cents goes toward helping children.

Written by

Written by