The Red Sea crisis: tracking the volatile security situation

The deteriorating Red Sea security situation caused by Houthi attacks and hijackings on commercial vessels has led to several major companies in the maritime and oil industries, to shy away from the Red Sea, and instead use the much longer, and costly route around Africa.

Securing the area and restoring normal commercial shipping activities has led governments and security agencies to launch Operation Prosperity Guardian, making the need to track vessel activities anywhere as they happen, in real-time and with high accuracy, more important than ever.

Red Sea shipping, a vital maritime route

The Red Sea, located between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, to which it connects via the Bab el Mandeb straight and the Gulf of Aden. Although relatively small compared to other seas and oceans, it is of vital importance for the maritime industry, and the global trade. The Red Sea shipping lane, linking Asia to Europe via the Suez Canal, provides vessels with a direct route between the two continents, shortening the journey almost by half, as compared to traveling around Africa via the Atlantic Ocean. Because of its geolocation, it is paramount for defence forces to protect it. Considering that 12% of global trade passes through the Red Sea and 30% of global container traffic, one understands why any disruption to this vital shipping lane has major implications for the world economy. To protect major waterways, defence institutions need to be able to make key decisions and rapidly respond to emergencies with granular and real-time data. Peak situational awareness and speed are key.

Deteriorating Red Sea security situation

The war that erupted early October between the militant Palestinian organisation Hamas and the Israeli Defence Forces has had an unexpected impact on the maritime traffic travelling through the Red Sea. Since November of last year, the Houthi rebels, who control swats of Yemen along the shores of the Red Sea, conducted repeated attacks on commercial vessels in support of the Palestinian cause.

Mid-November the group announced that it would target Israeli ships, ships with links to Israel, or ships heading towards Israel. On November 19th, it managed to capture the Japanese operated cargo ship with links to an Israeli businessman, the Galaxy Leader. Days later another ship was targeted in the Gulf of Aden. This action was foiled by a US naval vessel which then appeared to be targeted by two suspected Houthi missiles. A further security escalation occurred in mid-December when Houthi rebels launched a series of attacks. Missiles reportedly struck three commercial ships sailing through the Red Sea. Meanwhile, a US naval ship shot down three drones belonging to the Houthi’s.

By the end of the year, 23 Houthi attacks were recorded on international shipping in and around the Red Sea. At the time of writing there is no end in sight to such attacks. Major shipping and oil companies such as BP, Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd, MSC, CMA-CGM, Evergreen Line have therefore reduced or completely halted their vessels from sailing through the Red Sea.

Commercial vessels seeking protection

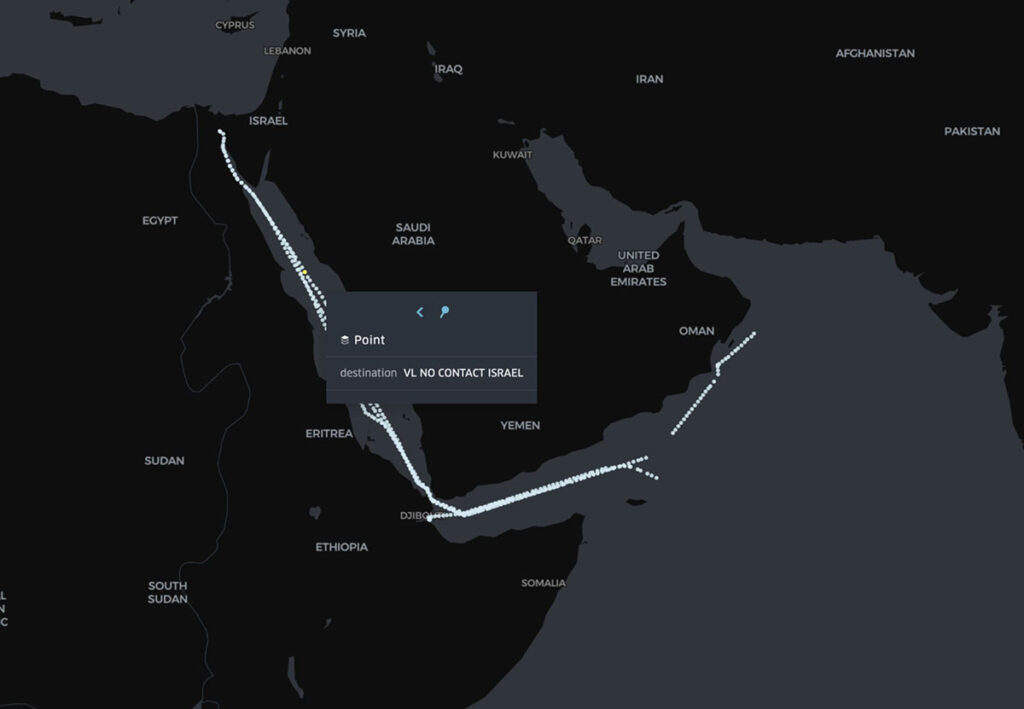

Some vessels still sailing through the Red Sea changed their destination in the AIS data destination field to ‘VL NO CONTACT ISRAEL’ in the hope that they would be able to sail safely through the area and protect themselves from Houthi attacks.

Another observation from the AIS data destination field are the mentions of ‘ARMED GUARDS ON BOARD’, the use of which increased significantly towards the end of 2023 compared to the same time in the previous year. These mentions are aimed to discourage potential hijackers.

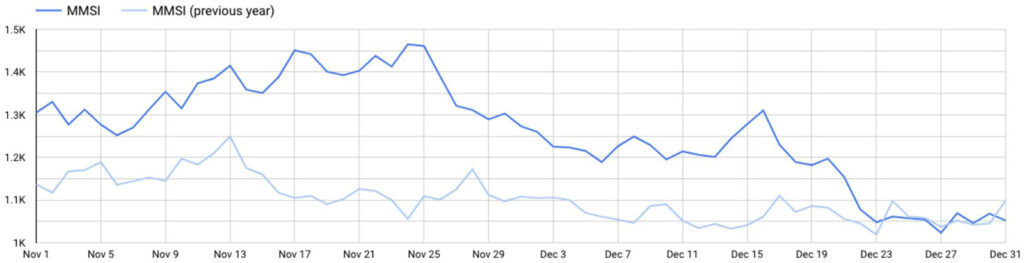

The below graph including Historical AIS data shows that over the course of 2023 maritime traffic in the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden, and the Gulf of Suez has been considerably higher than in the previous year. Upon the Red Sea attacks starting however, a decline in traffic is noticeable. A further sharp decline in traffic is showing from the 16th of December resulting in 2022 traffic surpassing 2023 traffic in a year-on-year comparison by the 23rd of December.

Light blue line – traffic in 2022 (Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Gulf of Suez)

Dark blue line – traffic in 2023 (Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Gulf of Suez)

As the attacks persisted, vessels heading towards the Suez Canal decided to divert away from the Red Sea. In some cases, their diversion did not happen early on in their voyage, but only by the time those vessels were already quite far in the Gulf of Aden, meaning their U-turn and journey around Africa comes at a significant cost. A similar situation occurs on the other side of the Suez Canal in the Mediterranean Sea.

Gulf of Aden: ship making a U-turn

Mediterranean Sea: ship making a U-turn

Ships diverting around Africa

The current security risks that sailing through the Red Sea poses, and the economic consequences of diverting vessels away from the Red Sea, led to Western navies intervening.

Learn more about Real-Time AIS, Historical AIS, and Enhanced Satellite AIS data

Get in touch with us for more information on Real-Time AIS, Historical AIS, and Enhanced Satellite AIS data, some of which are unique data solutions only available from Spire Maritime.

Written by

Written by