Peak wildfire season ahead in US: When and where will conditions be most active?

- Reflecting on 2023's wildfire season

- Impact of above-normal precipitation and carryover fuels

- Adding fuel to the fire

- Winter snowpack and its influence on fire season

- The North American Monsoon's role on wildfire season

- El Niño-Southern Oscillation transition and its effects

- Wildfire risk outlook for late summer to fall

- Using Spire's Soil Moisture Insights to assess wildfire risk for businesses

As summer continues, wildfires are becoming a more pressing risk for communities and businesses across the United States, especially across western portions of the contiguous US and Hawai’i.

This late summer and fall have the markers to be quite an active wildfire season, as a result of significant carryover fuels in many regions because of last year’s statistically weak fire season, ongoing drought conditions, low winter snowfall, and impacts from climatological cycles such as the North American Monsoon (NAM) and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

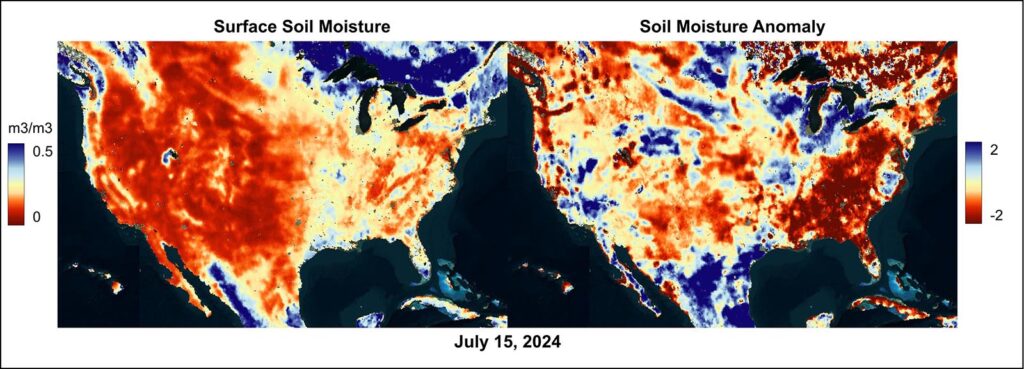

Surface soil moisture data (left) from July 15, 2024, shows dryness across much of the Western US, the Great Plains, and parts of the Eastern US. The anomaly map (right) highlights significant below-average soil moisture levels, depicted in deep red, from New England to the mid-Atlantic and Southeast, parts of the Four Corners, around California’s Bay Area, and the Pacific Northwest. The anomaly map also depicts below-average soil moisture on leeward side of the Hawaiian Islands.

Reflecting on 2023’s wildfire season

To look ahead, we must begin by looking back. The National Interagency Fire Center’s report for 2023 showed that last year was one of the least active fire seasons on record, with the fewest number of acres burned at 2,693,910 and the third-lowest number of individual fires at 56,580. However, individual wildfires were still massively destructive and costly, despite the overall reduced risk across the nation.

The Gray Fire and Oregon Road Fire in Spokane County, Washington, destroyed a combined total of 366 residential homes and resulted in the deaths of two people, according to the Washington Department of Natural Resources. The devastating Maui wildfires destroyed over 2,200 structures, killed more than 100 people, caused major economic losses estimated at about $5.5 billion in damages, and impacted tourism, the US Fire Administration said in a report.

The 2024 fire season has already been destructive, with the Park Fire in northern California ranking among the top five largest wildfires in the state’s history. As of early August, it continued to grow. According to the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), 2024 has recorded more than 28,000 wildfire incidents, burning about 4.5 million acres. Compared to 2023, more acres have burned this year despite having about half the number of fires, indicating a higher occurrence of large or difficult-to-contain fires.

US wildfire statistics for the last 10 years:

| Year | Fires | Acres |

| 2023 | 56,580 | 2,693,910 |

| 2022 | 68,988 | 7,577,183 |

| 2021 | 58,985 | 7,125,643 |

| 2020 | 58,950 | 10,122,336 |

| 2019 | 50,477 | 4,664,364 |

| 2018 | 58,083 | 8,767,492 |

| 2017 | 71,499 | 10,026,086 |

| 2016 | 67,743 | 5,509,995 |

| 2015 | 68,151 | 10,125,149 |

| 2014 | 63,312 | 3,595,613 |

Data for the number of wildfires and acreage burned across the US over the past decade. (National Interagency Coordination Center)

Impact of above-normal precipitation and carryover fuels

Above-normal precipitation in 2023 is attributed to the reduced number of wildfires, especially for Western regions. This increased precipitation, however, has meant that some places, especially parts of Idaho, Nevada, and Utah, are going into the 2024 fire season with a high amount of carryover fuels, or exceptionally dense brush and grass, which is now available for burning in 2024.

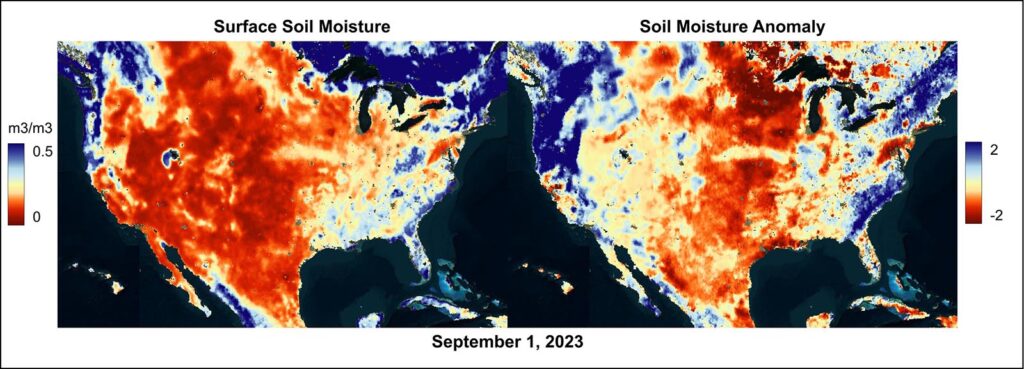

Surface soil moisture data (left) from September 1, 2023, showed dryness in parts of the Western and Central US, with a small dry area in the Northeast. The anomaly map (right) highlighted significant below-average soil moisture levels, depicted in deep red, in the Upper Midwest and along the Northeast coast. Soil moisture anomalies for the West Coast and Southeast were near normal to above average.

Comparing soil moisture from 2023 to 2024, significant differences emerge in the anomaly maps, which compare the soil moisture levels relative to the 10-year historical average. By September 2023, soil moisture levels in the West and Southwest were generally near normal to below normal. In contrast, 2024 shows many more areas with below-normal soil moisture, especially in the Pacific Northwest and northern California.

Additionally, the Southeast exhibits far below-normal soil moisture this year, whereas, by late summer 2023, much of this region had near-normal to above-normal soil moisture conditions. In the Great Plains and Midwest, soil moisture anomalies are less noteworthy this year despite conditions remaining generally dry. Notably, Hawai’i displays much drier anomalies and surface soil moisture this year, particularly on the leeward sides of the islands, raising concerns given the magnitude of the 2023 wildfires in Maui.

Adding fuel to the fire

Drought is an indicator of heightened fire risk. Parts of northern Idaho have been in a long-term drought, which has contributed to above-normal fire risk this summer. A lack of rainfall not only increases the amount of dried vegetation, which makes excellent fuel for fires, but can also make containment of fires much more difficult, resulting in larger and more destructive wildfires. Mountainous regions, such as northern Idaho, present an additional challenge as the terrain can make access to ongoing fires difficult, which in turn can result in increased fire risk.

Climate change is increasing the intensity and frequency of flash drying of fuels. For instance, the Maui fire in 2023 was driven by the flash drying of fuels and an extreme wind event. It should be noted that the types of fuels available for burning play a significant role in wildfire behavior. Also, nearly 85% of wildfires are caused by humans in the US, according to the National Park Service. Additionally, the escalation in destructive wildfires is due to increased building and populations in wildland areas, known as the Wildland Urban Interface. Wildfires are a big part of Earth’s natural cycle, but if we continue to build and live in areas that are prone to wildfires, it will only increase the risk of being impacted by wildfires.

Of course, the opposite is true also. Areas where drought is non-existent due to above-normal precipitation totals will face a lower risk of wildfires. This was the case for places such as northern California, which was not experiencing drought or abnormally dry conditions in the spring and early summer, resulting in wildfire risk being below normal into July. However, an expected drier end to summer will continue to elevate the fire risk to near normal or perhaps slightly above normal for parts of the northern Central Valley of California and into portions of the northern Sierra Nevada.

Additionally, record July heat in northern California and the Pacific Northwest has set the stage for more wildfire vulnerabilities in the coming weeks.

Winter snowpack and its influence on fire season

For mountainous regions, winter snowfall, and the rate at which it melts can be a defining factor in the following summer’s wildfire risk. The Cascades this past winter saw lower-than-average snowpack development, however, the snowpack that did develop was slow to melt. That has resulted in a slightly delayed start to the fire season across parts of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, as green-up, or new plant growth, was delayed due to snow cover. A summer continues, and this growth begins to dry out as above-normal temperatures are expected late this summer, fire risk will increase for these regions.

The North American Monsoon’s role on wildfire season

The North American Monsoon (NAM) is also a contributing factor to wildfire development, especially across the southwestern US, as this helps to fuel the majority of summer rainfall for places like Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado. A weaker-than-average monsoon will result in drier soil and more dry fuels, and any fires that ignite will be harder to contain without rainfall to help out. On the other hand, a stronger-than-average monsoon season will do the opposite and help reduce the risk of wildfire development. Although the NAM impacts several states, it accounts for more than 50% of the annual rainfall in New Mexico and Arizona. With the Climate Prediction Center season outlook predicting below-normal rainfall and above-normal temperatures from August to October, wildfire risk may be elevated across Arizona and New Mexico.

One other risk to consider is the fact that thunderstorms triggered on the periphery of the NAM moisture can sometimes produce frequent lightning with little rainfall, and these dry thunderstorms often ignite wildfires.

El Niño-Southern Oscillation transition and its effects

Meanwhile, a transition is occurring in the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). El Niño ended earlier in the summer, and ENSO-neutral conditions now prevail. La Niña conditions are likely to develop between August and October. Some of the climatological changes associated with the development of La Niña may lead to localized impacts on wildfires.

Wind events are a major driver for wildfire spread and can make existing fires incredibly difficult to contain. La Niña may enhance trade winds, which increases the risk factor in places such as northern California and Hawai’i, increasing fire development risk in the late summer.

Santa Ana winds in Southern California can be a driver of wildfires from September to March, although research has shown that El Niño, rather than the predicted La Niña, tends to increase the intensity of these wind events. Still, Santa Ana winds can especially influence wildfire spread as they are characterized by their dry nature, originating from the deserts of the Southwest, and incredibly high speeds. Combined with the warmer and drier weather associated with La Niña in the Southwest, heightened wildfire risk in the fall and winter combined with the arrival of Santa Ana winds could result in very fast moving and destructive fires.

Across parts of the Southeast, especially across higher terrain, the transition period to La Niña has often resulted in warm and dry falls and winters, which could increase wildfire risk. However, the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) says long-term model guidance is mixed on what this fall could look like for the region.

In the Northwest, a transition to La Niña is typically associated with cooler and wetter ends to the fire season, but there can be exceptions. One such exception was in 2016. In both the Northwest and the Southeast, the NIFC reports similarities to that 2016 season, and a comparison to that year may give us an idea of what to expect this fire season. There was also a delayed start to the 2016 monsoon season, which may occur again this year with below-normal precipitation across New Mexico and Arizona.

To put it in context, 2016 was, like 2023, a year considered below average for wildfires. NIFC reported that the US saw 92% of the 10-year average of reported wildfires, and 79% of the 10-year average of acres burned in 2016. That year, Alaska and the Southwest endured an above-normal number of wildfires, while the Rocky Mountains, Southern California, and the South saw above-normal acres burned.

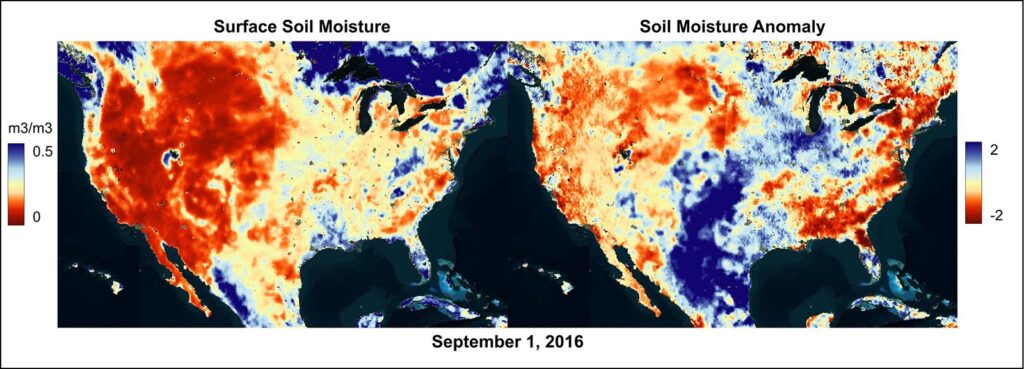

Surface soil moisture data (left) from September 1, 2016, indicated dryness in the interior Northwest, California, the northern Plains, and parts of the Eastern US. The anomaly map (right) showed significant below-average soil moisture levels in a few zones of the East, depicted in deep red.

Comparing the soil moisture anomalies for 2024 and 2016 reveals some clear similarities. The most notable similarity is the below-normal anomalies across the Southeast and along the East Coast. Although these anomalies are stronger this year, this pattern correlates with the NIFC’s assessment that the fire season in the Southeast may resemble that of 2016. In 2016, the Great Plains and Midwest had larger areas of above-average soil moisture conditions compared to both 2023 and 2024, which could explain the lower-than-normal wildfire statistics that year. Meanwhile, the below-normal anomalies in the West and Southwest this year appear stronger than those in 2016.

Wildfire risk outlook for late summer to fall

Overall, the wildfire risk is expected to shift through the remainder of summer and into the fall. August will bring the most widespread above-normal fire risk, mainly situated over southern Oregon, Idaho, northern Nevada, and Utah, where high amounts of vegetation will be ready to burn once they dry out and above-normal temperatures are expected. Parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and southeastern Colorado are also expected to see above-normal fire risk in August, as rainfall is expected to be below average. These same regions will continue to see increased fire risk in September, with fire risk in California shifting southward to the southern coastline, where above-normal fine fuel loading is expected as well as above-normal temperatures and drier conditions. Elsewhere in September, the fire risk will return to normal across much of the country, with the exceptions of Southern California, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Virginia, and West Virginia at above-normal risk.

Wildfires can be quick to spark, fast to spread, difficult to contain, and potentially present extreme danger to homes and businesses. Where you are located can change your wildfire risk level, but on the back of a quiet 2023, there is a lot of unburned dense shrubbery on tap.

Since the Western US is generally expected to be warmer and drier, and slight impacts from a transition from ENSO neutral to La Niña are anticipated, there are several spots where wildfire risk will be heightened heading into late summer and fall. Any business owners and homeowners in areas prone to wildfires should always be prepared to take action quickly when the situation arises.

Using Spire’s Soil Moisture Insights to assess wildfire risk for businesses

There is a strong correlation between the timing and location of low soil moisture conditions and an increase in fires. In general terms, fires are more likely to occur in drought-affected areas and during dry seasons. Spire’s Soil Moisture Insights can be leveraged as a tool to weigh potential wildfire risk.

Dry soil is linked to more fires, but fires can also cause dry soil, affecting soil water availability for agriculture, and negatively impacting crop health and production. Satellite-based soil moisture and fire observations can aid local governments, response agencies, and other businesses in better anticipating and preparing for an active fire season, and aid in tracking the potential impact of fire on soil water availability and crop production.

Written by

Written by