Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea: Mitigating its risks with AIS data

The current security situation in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden caused by Houthi attacks on vessels has led to many ships avoiding the area and instead divert away from it and chose alternative routes. The most common alternative journey between Asia and Europe is to sail around Africa.

However, sailing around Africa comes with its own set of risks, mainly from piracy in and around the Gulf of Guinea.

The Gulf of Guinea, a hotbed for piracy

Sailing through the Gulf of Guinea, which stretches from Senegal in Western Africa to Angola in Southern Africa, isn’t hazard-free and comes with its own set of security issues such as drug trafficking, oil bunkering, illegal fishing, and kidnapping (1). The most notable risk comes from piracy. Even though piracy in the Gulf of Guinea has decreased in the last few years, from 81 incidents in 2020, to 35 incidents in 2021, and 19 incidents in 2022, it is now on the rise again, with 22 incidents in 2023. According to the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) (2) the Gulf of Guinea accounted for three of the four reported hijackings worldwide, and 75% of reported crew hostage takings. The IMB report also noted that crews continue to be harmed and threatened. Pirates in the Gulf of Guinea are known for their intimidation tactics and violent modus operandi. Kidnappings, torture and shootings of crew members are not uncommon.

Halfway through 2023, the IMB (3)(4) had warned of renewed piracy activity in the Gulf of Guinea and as such called for continued vigilance and for international security efforts to prevent resurgence to the level of activity seen in previous years.

Shipping threats in the Gulf of Guinea becoming a global concern

The goals and the way piracy are carried out have changed over the recent years.

Indeed, not only are West African countries affected by these acts of piracy, but the wider maritime community is as well. So much so that it has become an issue of global concern since 2011. While the vast majority of incidents used to be categorized as simple maritime robberies, since the last decade, attacks have become more organized and sophisticated. The pirates now rely on extensive networks and have connections with corrupted government officials (5), businesspeople, and armed transnational mafia groups. Their incursions have increasingly been aimed at acquiring cargos containing petroleum. According to a study from the European Parliament, this is linked to the discovery of offshore hydrocarbons in the area, from which only governments, local elites and oil companies have profited, leaving many excluded from the wealth that it brings. Consequently, some people have turned to illegal maritime activities such as ‘petro-piracy’.

Piracy does not only entail a huge security risk for ships and crew members but is also putting assets at risk, including oil, and as such has a major economic impact. Global piracy costs the world economy tens of billions of dollars annually according to a 2013 World Bank study and a recent CNBC article (6).

Petro-piracy and the international security response

Petro-piracy activities result in tankers being the target of attacks in the Gulf of Guinea and this was no different over the course of 2023 and early 2024. Some examples include the incidents involving the Success 9 (7) in April 2023, and more recently the Hana I (8). Reports have been that pirates often steal a portion of the vessel’s cargo and hold crew members as hostages. Further examples evolve around the Monjasa Reformer, a Liberian-flagged tanker, which at the time had 16 crew members on board.

The Monjasa Reformer (9) was attacked by 5 armed men on the 25th of March of last year while sailing 140 nautical miles west of Pointe Noire in Congo. This information was picked up by the Maritime Domain Awareness for Trade – Gulf of Guinea (MDAT-GoG), which is a cooperation centre between the UK Royal Navy and the French Navy. Its primary task is to contribute and maintain coherent maritime situational awareness in the central and western African maritime areas.

A day after the attack, a French Navy patrol ship was sent to the tanker’s last known location. AIS information data shows that at the time of the attack the Monjasa Reformer started drifting and eventually stopped emitting AIS data altogether, which made it more difficult for the French Navy to locate the vessel.

Four days after the attack, the French Navy was able to locate the tanker off the coast of Sao Tomé and Principe, approximately 90 nautical miles south of Nigeria. The pirates had kidnapped 6 of the vessel’s crew members.

Mitigating security risks with AIS data

By combining historical AIS data with other relevant information, such as global events or economic indicators, one can mitigate risks by uncovering potentially dangerous maritime areas and make informed decisions as to avoid those areas or not.

When the decision is taken to sail through maritime areas with a heightened security risk, as is the Gulf of Guinea, it is essential to have access to AIS data in real-time. Not only commercial companies transporting commodities such as oil, minerals, and other products benefit from real-time AIS to track their vessels and know where they are located in real-time at any given time, but also for security missions such as the MDAT-GoG to enhance the understanding of maritime activities, support swift decision-making for rescue missions, and ensure security and compliance.

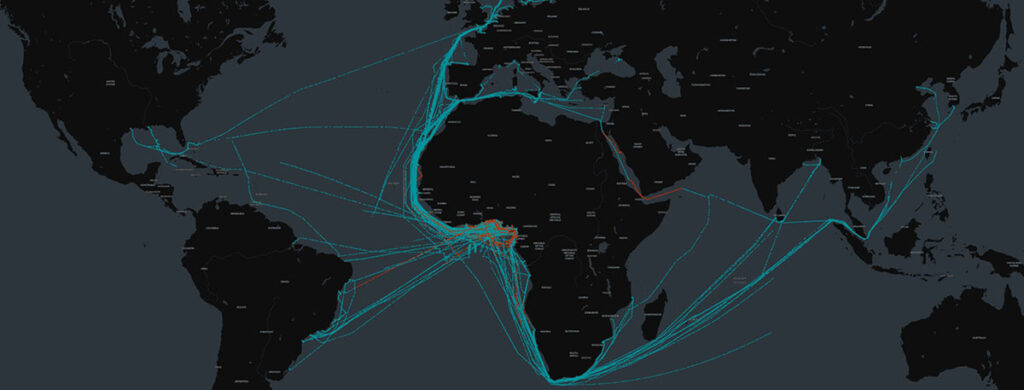

Another protection mechanism for vessels sailing through risky areas, which was recently seen in the Red Sea to avoid being attacked by Houthi rebels, is also being detected by analyzing AIS messages from ships travelling through the Gulf of Guinea. This technique consists of changing the AIS destination to ‘armed guards on board’, or any iteration of it, in order to discourage pirates to attack. Below image is an extract from maritime traffic in the Gulf of Guinea between December 1st, 2023 and January 15th of this year. The vessel tracks shown in red are the ones that changed their destination to ‘armed guards on board’.

When looking at this dataset on a global scale (image below), we can see that changing the destination to ‘armed guards on board’ only happens when approaching a high-risk zone (see the red areas around the Gulf of Guinea and the Red Sea). Once the vessel has successfully sailed through that zone, it would change the destination value back to the actual name of the port it is heading to. In the below image this is represented by the blue vessel tracks.

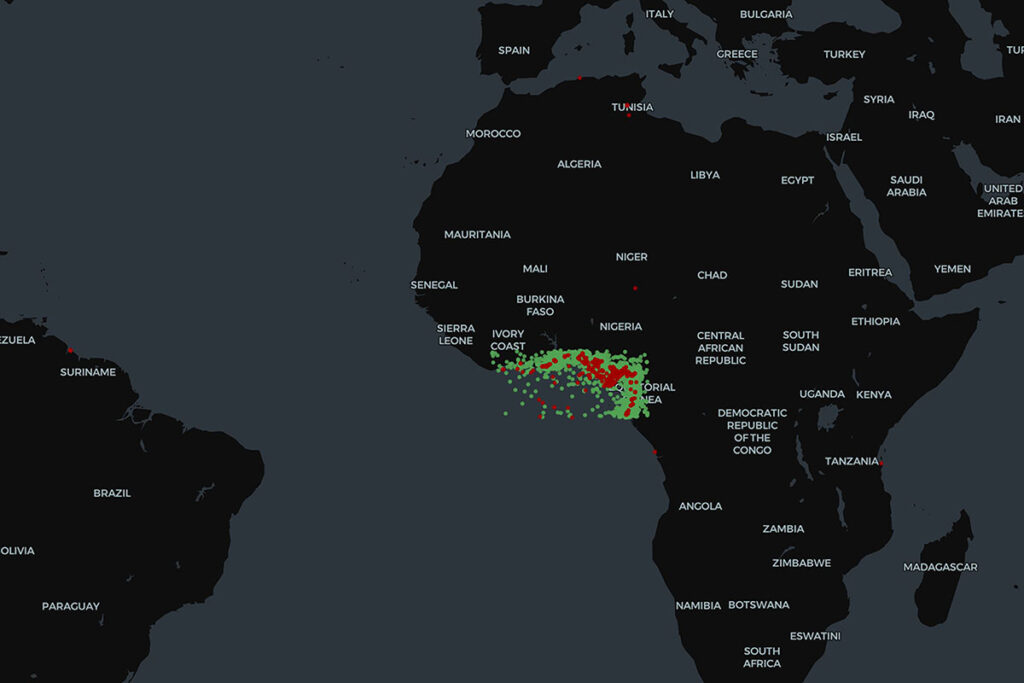

A final tactic that vessels use to hide from pirates and protect themselves from potential malicious behaviour is by not transmitting any location in their AIS messages or transmitting wrong information. AIS Position Validation was able to detect vessels in the Gulf of Guinea that are not reporting any location. In the image below those are visualized by the green dots. The red dots on the other hand are also vessels in the Gulf of Guinea but reporting to be somewhere else in the world.

Learn more about Spire Maritime’s AIS data sets

Get in touch with us for more information on Standard-AIS, Real-Time AIS, AIS Position Validation and Historical AIS data, some of which are unique data solutions only available from Spire Maritime.

Sources:

- Mica Center – Maritime Security Annual Report 2023

- ICC International Maritime Bureau – New IMB report reveals concerning rise in maritime piracy incidents in 2023

- ICC International Maritime Bureau – IMB raises concern on resurgence of maritime piracy and armed robbery in Gulf of Guinea in 2023 mid-year report

- The Maritime Executive – IMB Warns of a Resurgence in Gulf of Guinea Piracy

- International Journal of Research and Innovation in Applied Science

- CNBC – State of Freight

- Bloomberg – Singapore Says Missing Oil Tanker Found Off Ivory Coast

- TradeWinds – Crew members kidnapped in Gulf of Guinea tanker hijacking

- AP News – 6 tanker crew members seized by pirates freed in W. Africa

Written by

Written by