Ten ports vital to modern France

As a nation with a long history as a maritime power and economic powerhouse, France’s ports are both historic and key cogs in the modern economy of the entire European Union.

With long, independent coastlines facing two major bodies of water—the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea—France’s ports handle a wide variety of goods that traverse the globe as they move to and from the French Republic. Additionally, there is a well-developed inland waterway system that brings goods to the capital Paris and transits agricultural products from the interiors’ rich farmlands.

Reviewing ten of France’s most important ports takes one through the rich history and modern operation of one of the world’s most diverse maritime infrastructure systems. This starts on the northern coast, where a series of French ports begin the chain that runs up to the Baltics and makes the English Channel the busiest seaway in the world. The western coast faces the open Atlantic and provides direct access to the Americas and Africa. It also includes the Mediterranean coastline, which was part of Europe’s first great modern trade network, richly captured by the eminent French historian Fernand Braudel in his The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Finally, France has an ancient river and canal system that, taken as a whole, is a vital inland waterway.

France’s seaports and inland waterways are fully integrated and their smooth collaboration is vital to the modern French economy. The nation’s primary northern port, Le Havre, is managed under the HAROPA arrangement that includes the Seine’s inland ports of Rouen and Paris and is meant to make the Seine waterway a smart corridor that embraces digital solutions and smart data to enhance port operations. Although steeped in history, France’s ports are on the cutting edge of modern port management and full integration with contemporary logistical systems.

“The HAROPA partners handle 125 million tons of cargo a year. Through HAROPA, we are working to deliver an integrated logistics solution for the Seine corridor,” explained the HAROPA Port of Le Havre Information Systems Manager Jérôme Besancenot when HAROPA joined the International Port Community Systems Association in 2020. “We want to create the port of the future and provide a ‘smarter’ territory through a new integrated industry and port model … The port is at the heart of the supply chain; we have to provide standard interfaces if we want to be connected tomorrow with other partners, and in order to interact via Maritime Single Windows between countries.”

Ocean ports

Port of Le Havre

The anchor of France’s Atlantic ports, Le Havre is the nation’s second-largest and is ranked fifth in Northern Europe. It is intertwined with approximately 650 other world ports and handles over 6,000 ports of call annually and serves as the country’s busiest container port (including as the world’s top wine and spirits export hub). It is also a major transportation connection to Great Britain, with regular ferry runs to Portsmouth, England, and it also serves the world’s premier cruise lines.

Situated on the Seine Estuary, much of the area around the port is a maritime protected area, befitting a region rich in aquatic and bird species. HAROPA operates it under a “green port” policy that minimizes its environmental impact.

Port of Deauville

Across the Crique de Rouen from Le Havre, where the River Seine empties into the ocean, the Port of Deauville serves as a home harbor and port of call for up to 850 yachts. Not a commercial port per se, it is a tourism hub that is considered one of Europe’s finest marinas and tourist destinations.

Port of Calais

Even after the 1994 opening of the Channel Tunnel, which terminates in Calais on the French side, the city’s port continues to be France’s busiest maritime passenger terminal. In 2019, prior to COVID-19 and Brexit, over 8.6 million passengers passed through from ferries that link it with Dover. It is mainland Europe’s busiest car ferry port. The city and its harbor have long been a crucial link between Great Britain and the continent, in peacetime and war. One of the best-known works of Auguste Rodin, the sculpture “The Burghers of Calais,” memorializes an incident from the Hundred Years’ War between England and France at a place that has long been pivotal to the region.

Port of Dunkirk

Just 30 miles up the coast from Calais, Dunkirk is famous for being where Allied forces evacuated when Germany rolled into France during the blitzkrieg at the beginning of World War II. Today it is France’s third-ranked port, specializing in bulk industrial cargoes and roll-on/roll-off (ro-ro) traffic, and is a key hub in the Brussels-London-Paris transport triangle.

Port of Brest

Serving Brittany, the westernmost region of France, the port of Brest has a long history and today is an important shipbuilding and repair center, along with handling fertilizers, paper products, and agricultural items. Likely the port from which French explorers first sailed for North America, it has been the home of the French Naval Academy since 1830 and is a significant port for the French Navy.

Port of La Pallice

South of Brest facing the Bay of Biscay is La Pallice, a deep-water port in La Rochelle, which handles over 8 million tons of cargo annually. Serving France’s agricultural heartland, it is the nation’s second-largest grain-export portal and is also a major hub for oil and forest product imports.

Port of Marseille

France’s busiest port, and one of Europe’s ten busiest, is Marseille Fos Port. With two main facilities separated by about 30 miles, it handles 1.5 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), 79 million tons of goods, and nearly 10,000 ships annually.

Since France produces very little oil domestically, its proximity to the Suez Canal makes it the country’s major oil port, which includes petroleum refineries and chemical processing operations. More than 60% of France’s imported hydrocarbons move through Marseille, the third-ranked hydrocarbon port in Europe.

It also handles agricultural imports such as seafood, olives, and sugar. Being on the French Riviera also means it is a major tourist port hosting major cruise lines and smaller pleasure ships, as well as ferries to Corsica, Sardinia, Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. It is the Mediterranean’s fifth busiest cruise port.

Inland ports

Port of Lyon

The largest of a system of 22 ports running along the Rhône, a river that begins in Switzerland and empties into the Mediterranean near Marseille, Lyon’s port is one of Europe’s most popular river cruise hubs. With two container terminals, it also handles well over 10 million tons of goods and a significant amount of petrochemicals for eastern France. Much of the city’s wealth was originally built on its becoming Europe’s silk weaving center in the 15th century, an economic development premised in part on its direct access to the Mediterranean.

Port of Rouen

Located on the Seine between Le Havre and Paris, the Port of Rouen is Western Europe’s largest port for shipping grain cereals. Between the ocean and Rouen is the Parc Naturel Régional des Boucles de la Seine Normande, an over 200,000-acre protected area that serves as a buffer zone between the metropolitan areas. Not surprisingly, environmental protection is an important aspect of port operations.

Port of Paris

The Port of Paris serves the nation’s largest city and one of the world’s great metropolises. Both a hub for goods and passenger ships, it was France’s first inland port that could handle container ships and now processes over 125,000 TEUs per year. It is fully integrated into a rail, road, and pipeline network that serves all of central France while helping preserve the historic beauty of central Paris by handling a wide range of goods that would otherwise have to be transported by land.

Overview of the French maritime system

Most of France’s contemporary ports have long histories in the nation’s industrial, fishing, and military development. These ports were the gateways to France’s colonial empire and vital cogs in the nation’s long maritime rivalry with Great Britain.

Since Napoleon, France has been famous for its centralized public management, though today only 11 of the nation’s approximately 60 significant ports are publicly owned and managed. The current management structure follows reforms that occurred in 2004 and 2008. Prior to this, 23 ports were state-owned under the auspices of the Maritime Chambers of Commerce and Industry (CCI). Today there are eight state-owned, geographically distributed ports operating under the Grand Port Maritime, including Dunkerque, Le Havre, Rouen, Nantes Saint-Nazaire, La Rochelle, Bordeaux, and Marseille. The extensive inland waterway system is managed by Voies navigables de France ([Navigable Waterways of France], VNF).

The nation’s maritime system is also becoming ever-more closely aligned with its rail network as new modes of supply chain management and synergies develop, including the recent rail-river alliance between SNCF Réseau (which oversees France’s rail infrastructure) and VNF to better manage the operational complementarity between rail and river transport systems. Since an increasing portion of French imports has come to flow from the major Dutch and Belgian ports of Rotterdam, Zeebrugge, and Amsterdam since the full integration of the European Union, French ground transport is also more fully integrated with those of their neighbors.

Current congestion issues

Like ports and supply chain interests around the world, France’s harbors have been knocked about by COVID-19 and the resulting tumult that has hit global markets, including the fallout from the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Understanding the full impact of the last few years is still a work in progress, with the shifting of ports between status as major hubs and regional hubs ongoing. One recent study, entitled “COVID-19 as a Catalyst of a New Container Port Hierarchy in Mediterranean Sea and Northern Range” published in Maritime Economics & Logistics shows evidence that France’s ports took a hit (with Brexit perhaps another mitigating factor):

In 2020, Antwerp and Zeebrugge were the only [Northern Range] ports with a positive evolution compared to 2019, with + 0.9% and + 10.4% respectively … Further, the strongest declines occurred in Le Havre (− 18.9%), Dunkirk (− 15%), Liverpool (− 14.6%) and Felixstowe (− 10.2%).

Concerning the Mediterranean container seaports, our analysis underlines some clear trends. The COVID-19 impacts did not have the same gravity as for Northern ports. In spite of its negative growth (− 3.8%) in 2020, Piraeus consolidated its position as the fourth European container port followed by the two Spanish ports of Valencia (5th) and Algeciras (6th) … On the contrary, places such as Ashdod, Marsaxlokk, Genoa and Marseille, faced notable declines. Concerning Marseille, its collapse was particularly strange and it might be the cumulative consequence of strikes in 2019 (− 15.8%) and COVID-19 (− 53.5%) in 2020.

But 2021 has seen a strong rebound at French ports, with positive year-over-year growth at Le Havre (28%), Marseilles (13%), and Dunkirk (41%):

From the nautical access point of view, Le Havre’s Port 2000 facility is the favourite with masters of big ships in Europe. At a time when there is congestion and a great deal of waiting, Port 2000 can be accessed quickly, simply and efficiently in all weathers.

Like Fos-sur-Mer and Dunkirk, Le Havre is a port which enjoys exceptionally good natural conditions. Southampton, on the other hand, is heavily handicapped by navigating conditions in the Solent, which are often difficult in winter. Access to Hamburg and Antwerp involves costly and fastidious manoeuvring, while Genoa and Barcelona are ports which have always been hampered by their physical environments.

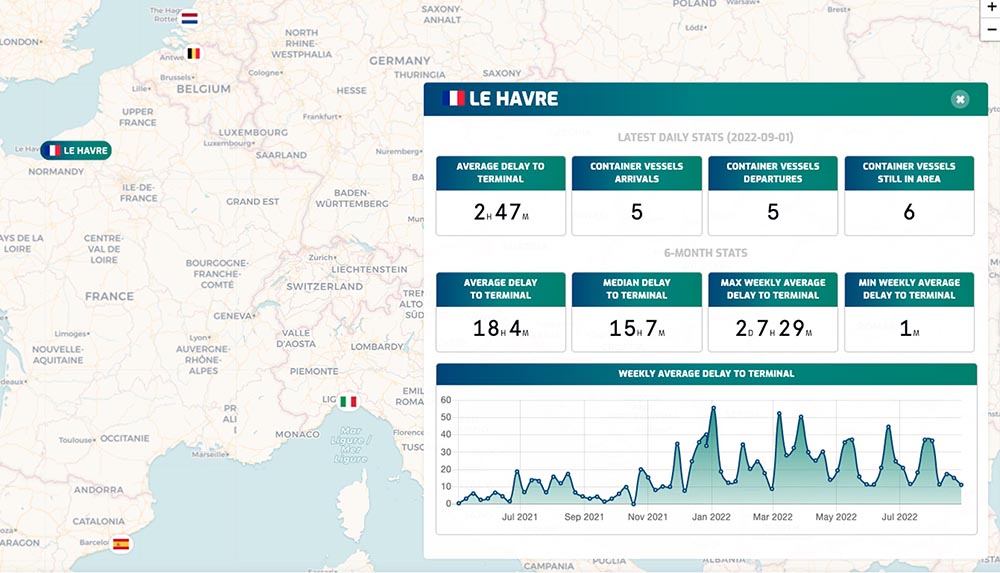

The “natural geographical advantages” that cut down on weather-related wait times and congestion, especially at Le Havre, are a strong point of French ports. As can be seen with Spire’s congestion tool for Le Havre, the average delay to terminal is currently only a few hours and the average over the past six months is under 24 hours.

But it’s been the nautical equivalent of a rocky road. This past summer saw significant congestion issues, including the container transport company Hapag-Lloyd introducing congestion fees at Le Havre and Marseille’s Fos-Sur-Me (as well as other European ports) due to operations grinding down due to labor shortages and related issues.

As with ongoing issues at ports in China and earlier ones at the Port of Los Angeles, COVID-19 has sent riptides throughout the supply chain that tools like AIS data can help alleviate, but not entirely cure.

But France’s ports, through the centuries, have seen it all. Marseille was one of the first European ports of entry for the bubonic plague in the late 14th century. Calais’s Port Boulogne was attacked by the British in 1804. Le Havre was extensively bombed during World War II. Eventually, the relatively minor in comparison challenges of COVID-19 are bound to fade.

Written by

Written by