Going green for climate change, one corridor at a time

Solving problems, especially big ones, is often a matter of breaking the multitude of issues one is facing into more manageable parts. And there is no bigger problem than reducing the amount of greenhouse gasses entering the Earth’s atmosphere.

It is only by implementing a myriad of zero carbon efforts spanning continents and economic sectors that, cumulatively, carbon emissions will be reduced enough to avoid the kind of catastrophic climate change that we’ve been getting a preview of this summer.

We are seeing this dynamic more and more. A piece of high-profile news was that the Inflation Reduction Act would likely pass through the US Congress and get to President Biden’s desk. Largely through a series of incentives to rapidly expand clean energy production and the transition to electric vehicles, the Act will drive down greenhouse gas emissions from the United States by 42% from 2005 levels by 2030. A significant slice of the pie.

Plans for the creation of the world’s longest green shipping corridor between the ports of Singapore and Rotterdam have also been a top story in maritime news. Linking two of the world’s ten largest container ports, the project will directly lessen the environmental impact of transport between one major European and one major Asian transport hub. It is also hoped that it will serve as a model for other such corridors between other large ports and build on the “Clydebank Declaration for Green Shipping Corridors” that was finalized at the COP26 conference in Glasgow, Scotland in late 2021.

Two mega-ports

The importance of these two ports cannot be overstated. According to the World Shipping Council’s rankings of 2020, Singapore ranks second and Rotterdam tenth as the busiest container ports in the world, with Singapore handling over 36 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) and Rotterdam over 14 million.

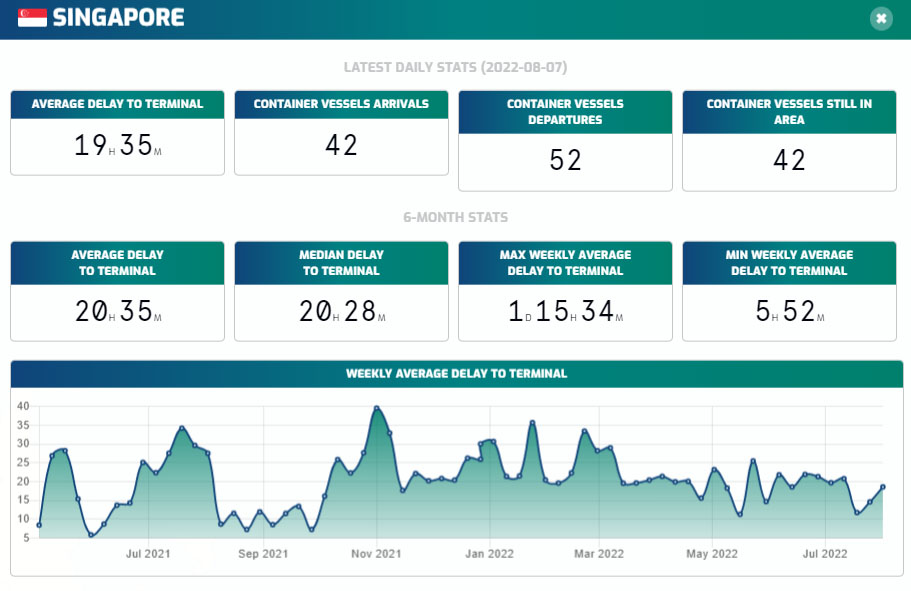

As can be seen with Spire’s congestion tracker, the port of Singapore (managed by the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore [MPA]) has maintained a steady flow of arrivals and departures in the last year and is regularly handling over 30 incoming and outgoing container ships daily. The port is an amalgamation of several terminals, including Tanjong Pagar, Keppel, Brani, Pasir Panjang, Sembawang, and Jurong terminals.

Given that it acts as a transportation hub between southeast Asia, China, India, and the rest of the world—including that, by some calculations, half of the world’s annual supply of crude oil transits through it—the port’s importance to the global supply chain cannot be exaggerated. Along with petroleum products and the vast number of TEUs it handles, Singapore’s port also serves as a regional vehicle trans-shipment hub and transfers steel products, copper slag, and cement. It also has a thriving cruise ship facility that hosts ships operated by several of the world’s major operators.

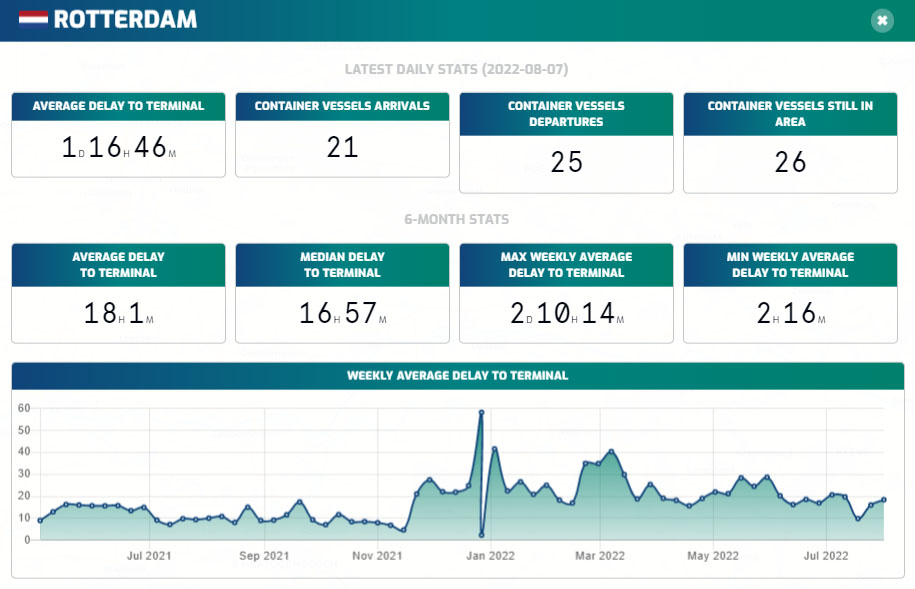

As can be seen, Rotterdam’s port (managed by the Port of Rotterdam Authority) is likewise handling a steady flow of arrivals and departures—about 40 container ships daily. The port is not only the major TEU transit port for Europe but is also hugely important to the petrochemical industry.

The largest seaport in Europe, the port covers over 40 square miles spanning several harbors, including Delfshaven, Waalhaven, Botlek, Europoort, and more recently reclaimed areas like Maasvlakte. It has long been one of the most innovative ports in the world and has long been a leader in robotics and automation (as fans of The Wire might remember from season 2, which first aired in 2003).

Given the vital importance and amount of traffic between these two ports, as each is the major TEU handler for their region, making their connection greener and less environmentally damaging would be a significant standalone accomplishment. If their work together also puts innovative solutions into the industry pipeline, normalizing what are currently more conceptual solutions, then that impact will be multiplied.

A green joint venture

The agreement is a memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the management firms of both ports. It calls for a coalition of shippers, fuel suppliers, and other industry stakeholders to develop solutions under two broad rubrics. The first is to develop alternative fuels that can be developed and improved to the point that they can replace fossil fuel power sources. A crucial aspect of such a transformation is bunkering ports, where ships get refueled, transitioning and incorporating the ability to handle new fuel sources into their existing infrastructure.

The second area is digitization efforts that can raise the efficiency of the maritime sector by optimizing the flow of goods, which in itself will lower the needed input of power to move goods between the North Sea and the strait connecting the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. By developing a standardized flow of data and e-documentation, the hope is to create a “digital trade lane” that maximizes efficiencies, including by fine-tuning just-in-time arrivals and departures between the ports. This will tap into ongoing efforts by the shipping industry to harness automatic identification system (AIS) protocols to improve maritime analytics and drive better decision-making.

The groundbreaking agreement between the ports is a culmination of the leadership teams of either end of this long supply chain linkage, both of which have come through the COVID-19 pandemic and the chaos it created for the shipping industry realizing that global challenges demand greater cooperation and coordination.

“Our role has changed in recent years … Originally, we were there mainly to manage the port. Now we’ve become a developer, initiator, pivot, leader, and participant. We need to play an active role. The challenges we face transcend value chains, permits, and regions,” the President and CEO of the Port of Rotterdam Allard Castelein told an interviewer from Marine Ingenuity, the online magazine of Van Oord. “Our role has grown and the way in which we play it is much more important than it was a few years ago. That gives our enterprise a lot of energy. It makes demands on people, but it also offers us and the businesses located in our port and industrial complex plenty of opportunities. Large companies are increasingly embracing the transition, and smaller ones are taking more and more steps to act sustainably.”

This latest endeavor fits well with the Port of Rotterdam’s legacy of innovation on the environmental front, such as its Dogger Bank wind farm/hydrogen project, which is expected to go online in 2030 and produce up to 7% of the European Union’s hydrogen fuel.

Likewise, the leadership of the port of Singapore also has a long track record of staying ahead of the technological curve. It was an early partner in the digitalOCEANS™ (Open/Common Exchange And Network Standardisation) platform and implemented its Maritime Singapore Green Initiative in 2019. Its green corridor partnership with Rotterdam is a natural outgrowth of its Maritime Singapore Decarbonisation Blueprint: Working Towards 2050 long-term plan.

As Ley Hoon Quah, the CEO of the MPA, said in a presentation to the Maritime SheEO conference last December, “On decarbonization, the sustainability movement is making waves across the global supply chain. We hear stronger advocates for green shipping and see shipping companies putting real money, investing into low carbon now. The momentum will only accelerate and we are already seeing so in Singapore with the setting up of the global center for maritime decarbonization (or GCMD). In short, with six major industry partners we will work within the industry to shape standards, deploy solutions, finance projects, and foster collaborations across sectors.”

Not all smooth sailing ahead

The challenges in meeting the goals of the green shipping and digital corridor plan are not insignificant. There is a range of alternative fuels and energy sources for the shipping industry, including ammonia, biodiesel, biomethanol, dimethyl ether (DME), liquefied natural gas (LNG), liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and various electric storage solutions that would power electric propulsion (though these are currently more feasible for short-haul regional transport).

The bottom line is that petroleum products are used because they are cheaper, more fully developed, and inherently more efficient per unit. But not cleaner, which is why we are where we are now.

But workable replacements for diesel will demand extensive research and trial and error, i.e. research and development, to get up and running to the extent necessary to be dependable enough to fuel voyages from Rotterdam to Singapore. It is a powerful moment as two heavyweights of the shipping world have thrown their collective weight behind developing solutions.

Digitization efforts, and the efficiencies they can wring out of the sector, are more advanced. Along with the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud computing, blockchain solutions, machine learning, and artificial intelligence, there has been heavy investment over the last decade to meet goals like mitigating marine shipping risk and safeguarding marine protected areas. But guaranteeing the quality of data and the ability of stakeholders up and down the system to fully access it will be a focus of further improvements. But luckily there is over a decade’s worth of historical automatic identification systems (AIS) data that has been built up that can serve as the analytical foundation for such efforts moving forward.

The MoU includes weighty participants like the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation, the Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Centre for Zero-Carbon Shipping, the Digital Container Shipping Association, CMA CGM, Maersk, MSC, Ocean Network Express, PSA International, BP, and Shell. Thus the Green and Digital Corridor project will have such a high profile that it will be able to attract financing, set up pilot projects, power digital twins (virtual scenarios based on real-world, real-time data), and better develop low- and zero-carbon fuels.

“Decarbonising shipping is an urgent climate action priority, which requires the collective efforts of the entire maritime sector. As a trusted global maritime hub, Singapore contributes actively to IMO’s efforts to make international shipping more sustainable, and global supply chains more resilient,” stated S. Iswaran, Singapore’s minister for transport and minister-in-charge of trade relations, stated as part of the public announcement of the program. “This MoU with the Port of Rotterdam demonstrates how like-minded partners can work together to complement the efforts of the IMO. It will serve as a valuable platform to pilot ideas that can be scaled up for more sustainable international shipping.”

Filling a role model’s sails

If these various, and powerful, threads can be woven together under the joint auspices of these two influential ports, then the bar for what is possible moving forward can be raised considerably.

The route between Singapore and Rotterdam is a colossus of the shipping industry, though just a piece of the gargantuan problem of global carbon emissions. But by introducing significant environmental mitigation into this vital supply chain corridor, new technologies and best practices can be developed that will eventually flow through the world’s many other shipping corridors. It will provide a multiplier effect that can make a momentous impact in reducing the amount of greenhouse gasses entering our planet’s atmosphere.

Written by

Written by